UK HOUSE OF LORDS INQUIRY: IS THE UN CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA STILL FIT FOR PURPOSE?

- varunk01

- Mar 29, 2023

- 15 min read

Updated: Mar 30, 2023

About the Author-

Lieutenant Commander Varun Kulshrestha is former Area Judge Advocate General, Indian Navy

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982, established rules governing all uses of the oceans and their resources. It includes traditional rules for the uses of the world’s oceans and seas and new legal concepts to address current concerns. The convention also provides the framework for further development of specific areas of the law of the sea.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982, established rules governing all uses of the oceans and their resources. It includes traditional rules for the uses of the world’s oceans and seas and new legal concepts to address current concerns. The convention also provides the framework for further development of specific areas of the law of the sea.

The then secretary general of the UN, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, described UNCLOS as “possibly the most significant legal instrument of this century” when it came into force in 1994. The convention includes provisions on:

· Navigational rights

· Territorial sea limits

· Economic jurisdiction

· Legal status of resources on the seabed beyond the limits of national jurisdiction

· Passage of ships through narrow straits

· Conservation and management of living marine resources

· Protection of the marine environment

· A marine research regime

· A binding procedure for settlement of disputes between states 168 states or bodies have ratified the convention

2. House of Lords International Affairs and Defence Committee report

Launching its inquiry in October 2021 the committee set out to examine whether UNCLOS was still “fit for purpose”. New challenges, such as rising sea levels and autonomous maritime vehicles, have arisen in the 40 years since the convention was negotiated. In addition, the committee wanted to investigate whether UNCLOS could address issues which have intensified in recent years, such as maritime security, human rights abuses at sea, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation.

The committee’s report assessed the convention overall before looking in detail at five areas:

· Maritime security

· Climate change and the environment

· Human rights and labour protections at sea

· Maritime autonomous vehicles

· Regulation of access to economic resources

2.1 UNCLOS

The committee highlighted that enforcing UNCLOS was a challenge, while recognising that this was true for all international law. The committee addressed ‘open registries’, in which countries allow foreign-owned or controlled vessels to use their flag. It said that these are usually “flags of convenience” (where a ship sails under the flag of a state with limited domestic regulation and enforcement capacity and few criteria for registration) and have led to a “jurisdictional vacuum” on the high seas. The committee argued that while UNCLOS had largely been successful, it should be updated and supplemented to address current challenges.

The committee recommended that the government:

· Use its influence in the International Maritime Organization, based in London, to explore ways to update the existing law

· Reconsider its position that annual meetings of the states parties to UNCLOS are not an appropriate forum to discuss substantive issues

· Take on a global leadership role in developing and enforcing the law of the sea, increasing its engagement with states and other actors

· Aim to increase the presence of British judges on institutions like the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea

2.2 Maritime Security

The committee said that many of the flag states with the largest registered tonnage did not have “the capacity or inclination” to “fulfil their obligations in terms of management, control or enforcement of their registered fleet”. The committee recommended that the government work with others to ensure there is a genuine link between vessels and the state in which they are registered, and to tighten the criteria of its own ship registry as an example to others.

On piracy, the committee said that UNCLOS and related instruments had “generally been successful” at tackling piracy. It acknowledged that piracy often originates on land and cannot be solved by agreements focused on the sea, but that supplementary agreements to UNCLOS had helped address the situation. The committee said the government should further enhance its capacity-building activities to assist other coastal states to address security threats including piracy and armed robbery at sea.

The committee highlighted that China has claimed exclusive jurisdiction over the South China Sea and rejected the principles of freedom of navigation and freedom of innocent passage as outlined by UNCLOS. The committee recommended that the government “continue to work with its partners and allies to protect and preserve the principles of freedom of navigation”.

2.3 Climate Change and the Environment

The committee noted that rising sea levels, caused by climate change, will affect the maritime entitlement provisions in UNCLOS. Maritime zones are areas where a coastal state has jurisdiction. Currently, they are calculated from baselines. The most commonly used baseline follows the low-water line along the coast of a state. The “traditional view”, according to evidence given to the committee, is that baselines move with the low-water line (they are “ambulatory”). As sea levels rise, the low-water line of many coasts will move inwards, reducing states’ maritime zones.

The committee said that the government should take a formal position that baselines should remain fixed in their current position. This would ensure that no states, including the UK and its overseas territories, lose their current maritime entitlements.

The committee also recommended that the government push for recognition of the oceans within the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. This would help to address the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change on the oceans and to strengthen the duties relating to land-based sources of pollution.

The committee also made recommendations on net zero shipping, fish stocks, the Arctic, and marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (also referred to as ‘BBNJ’).

2.4 Human rights and labour protections at sea

The committee highlighted that UNCLOS does not significantly address human rights. The committee said the government acknowledges that human rights at sea include a wide range of rights, and not just those concerning to labour conditions.

The committee said that under UNCLOS states have a duty to render assistance to persons in distress at sea, but “this obligation is increasingly side-lined by security and immigration policies”. The committee said that despite assurances from the government it was “not convinced that provisions relating to maritime migration and ‘turnaround tactics’ in the Nationality and Borders Bill [now the Nationality and Borders Act 2022] are compliant with the UK’s duties under UNCLOS”. It asked for the government to provide “a full assessment of the compatibility of the provisions in the Nationality and Borders Bill dealing with so-called forced turnarounds with the UK’s international responsibilities under article 98 of UNCLOS.

The committee argued that victims of human rights abuses that take place at sea often do not have access to timely or effective justice because of complex questions concerning legal jurisdiction. The committee said the government could investigate a range of mechanisms for addressing human rights abuses at sea, including port state controls, sanctions, and private arbitration systems.

2.5 Maritime autonomous vehicles

Maritime autonomous vehicles are a recent invention. They replicate many of the functions of traditional vessels, and provide new capabilities for operators, but do not necessarily need a crew to operate them. The International Maritime Organization has said that maritime autonomous vehicles can be divided into four classes. These range from ‘degree 1’ ships that have some automated systems but still have people on board, through to ‘degree 4’ where the ship is fully autonomous and capable of making its own decisions.

The committee commended the Royal Navy for adopting a “principle of equivalence”, treating autonomous ships the same as traditional ships. The committee said the government should monitor and work with others to regulate these technologies with regard to the principle of states being held accountable for their actions.

2.6 Regulation of access to economic resources

The committee recommended that deep-sea mining for resources should only be authorised when the minerals in question could not be recovered in sufficient quantity from existing products and when the deep-sea mining of those minerals was less environmentally damaging than extraction on land.

The committee also said that the government should establish a regional fisheries management organisation to address the current fishing challenges in the waters between the Falkland Islands and Argentina. It also suggested that the government strengthen the management and enforcement powers of regional fisheries management organisations more generally.

3. UK Government response

The government responded to the committee’s report on 9 June 2022. On 20 July 2022 the chair of the committee, Baroness Anelay of St Johns (Conservative), wrote to Lord Goldsmith of Richmond Park, a minister at the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, asking for further information in response to the report. The government responded to this letter on 15 November 2022.

In its response of 9 June 2022 the government said it agreed with many of the committees conclusions and was already working on many of the areas the committee had highlighted. There were, however, some areas where the government expressed a different view to the committee. These included:

· The government said that it did not agree the annual meeting of states parties to UNCLOS was an appropriate forum for discussing substantive issues, as since its establishment this meeting has been limited to discussion of budgetary and administrative matters and there was “no consensus” this should be changed.

· The government did not agree that the use of open registries, or flags of convenience, was a problem. It said the record of compliance with international conventions by vessels on open registries was not significantly worse than that of vessels on other registries.

· The government said it shared the concerns of the committee regarding forced labour and other labour exploitation abuses of those working at sea. It said, however, that it believed the Maritime Labour Convention 2006 and the International Labour Organisation Work in Fishing Convention 2007 (No.188) provided an effective framework to identify such abuses through port state control.

· The government said it intended to “take a cautious approach” to the question of whether baselines should be fixed in place in the face of climate change-induced sea-level rise. It said its general view was that baselines were ambulatory. It said it would keep this position under review.

On rendering assistance to persons in distress, the government said:

The safety of life at sea will always be the priority for any interceptions of small boats crossing the Channel to facilitate illegal migration, whether under current or future powers. The use of these powers will always be in compliance with international obligations including to promote safety and protect life. All immigration officers receive relevant training before being able to carry out their duties and exercise powers and must in any event exercise those powers in accordance with the requirements of the Human Rights Act [1998] as well as UNCLOS article 98.

The Ministry of Defence has taken over primacy in respect of Channel operations with regard to small boat crossings following the prime minister’s announcement on Thursday 14 April 2022. The turnaround policy and procedures have been withdrawn. If a decision were taken to use turnaround tactics in the future, it would only be after a full consideration of all relevant matters, including the evolving nature of the small boats threat, migrant behaviour and organised criminal activity; and new policies, guidance and operational procedures would need to be formulated at that point. The government’s position remains that the policy on the use of the tactic is lawful.

On China’s claims in the South China Sea, the government said:

In the South China Sea our commitment remains to international law, the primacy of UNCLOS, and to freedom of navigation and overflight. We take no sides in the sovereignty disputes and encourage all parties to settle their disputes peacefully through the existing legal mechanisms. China has never clearly articulated the basis of its so-called ‘nine dash line’ claim in the South China Sea. As the former minister for Asia [Nigel Adams] said in Parliament on 3 September 2020, if the claim is based on ‘historic rights’ to resources within the ‘nine dash line’, it is inconsistent with UNCLOS and the UK objects to any claim not founded in UNCLOS. The former minister for Asia also confirmed in that speech that the UK rejects any claim by China to approximate the effect of archipelagic baselines around groups of features in the South China Sea as inconsistent with UNCLOS. We welcome that negotiations have restarted between China and ASEAN on a code of conduct for the activities of claimant states in the South China Sea. We hope that an effective and substantive code of conduct is concluded but are clear that it should be consistent with UNCLOS and reflect and respect the rights and interests of third parties.

3.2 Letter from the chair of the committee to the UK government

In her follow-up letter of 19 July 2022, Baroness Anelay said there were areas on which the committee would like to seek further information from the government. She also said that on the areas of flags of convenience and human rights at sea the committee was “disappointed with the government’s response”.

· Annual meeting of states parties to UNCLOS: the government’s response said that the reason for not using the meetings for discussion of more substantive issues was because there was “no consensus” for this. Baroness Anelay asked if the government would investigate whether there was an appetite among other states for these meetings to change focus.

· Flags and registries: the committee said it was disappointed with the government’s response on flags and registries. It argued that “flags of convenience” result in poor law enforcement and the government should work to address this. It also said it was dissatisfied with the government’s assertion that it had been acceded to the 1986 Convention on Conditions for Registration of Ships because “the UK does not accede to maritime conventions until they have entered into force”. The committee asked the government whether it agreed with its assessment that lack of enforcement resulting from “flags of convenience” posed a “significant challenge” for maritime security.

· Human rights at sea: in her letter, Baroness Anelay raised several issues relating to human rights at sea, including:

o How the government intended to address the issue of where seafarers had access to methods to enforce their human rights

o Whether the government would clarify its position on whether human rights applied to all seafarers and not just workers, and whether these applied in all seas and not just UK territorial sea

o Flag states’ ability to enforce international law

o How the government intends to tackle the issue of forced labour and other labour exploitation abuses at sea

o Under what circumstances the government considers victims can bring a complaint or case in the UK

o Pursuing a unified approach to human rights at sea, on what basis the government considers “turnaround tactics” to reflect obligations under article 98 of UNCLOS

· Maritime autonomous vehicles: the committee said it was largely satisfied by the government’s responses in this section. However, it asked for further information on government plans to develop a legal framework for remotely operated and autonomous vehicles and whether consultation would be required before the secretary of state could update security regulations.

· The Arctic: the committee asked the government for more information on the actions the government was taking to monitor security developments in the Arctic and the UK’s progress towards joining the Central Arctic Oceans Fisheries Agreement.

· Climate change: in its letter, the committee asked the government to provide further detail on the types of solutions it envisaged to the problem of changing maritime entitlements as a result of sea level rise. It also asked for more information on the government’s assessment of the territories most likely to be at risk of loss of statehood or territory, and the number of people likely to be adversely affected.

· Deep sea mining: the committee asked for the government to provide the committee with a timeline of the expected publication of its report on deep sea mining and for the committee to be kept up to date on its progress.

· Regional fisheries management organisations: the committee asked the government to provide more information on its efforts to establish a regional fisheries management organisation in the southwest Atlantic.

· Subsea cables: the committee acknowledged the government’s agreement with its assessment that the security and resilience of subsea cables were a matter of importance. However, it asked for more information on how the government would ensure this and make the UK an attractive destination for transnational cables.

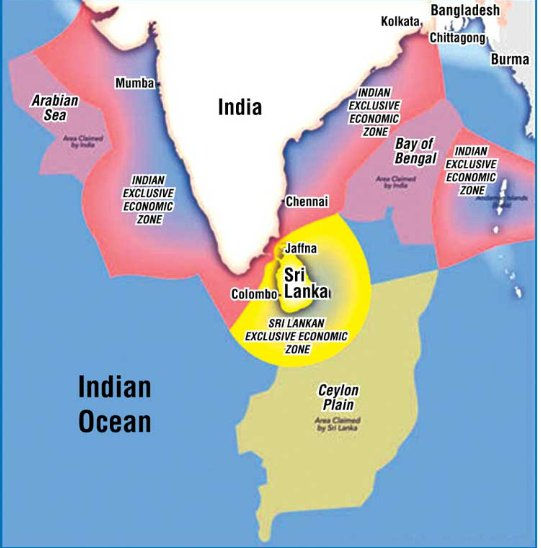

Concerns for India and ASEAN

India and the USA have fundamental differences in interpreting coastal states’ rights to stop foreign military ships from conducting military activities within their EEZ. India and China believe that states should have greater control over foreign military activities in their EEZ. The right of a coastal state to stop foreign ships from conducting military activities in its EEZ is not universally accepted. Such a right is not a formal part of international maritime law as articulated by the UNCLOS. Still, it appears in unilateral declarations made by countries when their accession to the convention. When India ratified UNCLOS in 1995, India declared that it was its understanding that the convention did not “authorize other states to carry out in the EEZ and in particular those including the use of weapons or explosions, without the consent of the coastal states”. India passed its domestic law — The Territorial Waters, Continental Shelf, Exclusive Economic Zone and Other Maritime Zones Act, 1976 (hereinafter referred to as Maritime Act) to support its views on the permissibility of foreign ships conducting military activities in its EEZ. Section 4(2) of the Maritime Act allows foreign warships to enter India’s EEZ after providing prior notice to the Central Government. The act does not specify for a “consent” or “permission”, and the prior notice requires no reply from the central government and is merely an intimation about the passage. Whereas the domestic law passed by the Chinese government requires “permission”.

UNCLOS is quite clear that while the exploitation of the resources of the EEZ and the seabed are the rights of the coastal state, there are no restrictions on the passage of foreign vessels, whether military or commercial, through them. Likewise, no prior notification is needed for “innocent passage” of military vessels through the actual territorial waters of the coastal state, i.e. covering a distance of 12 nautical miles from the coastline.

USA performed the Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in the Indian EEZ. The idea behind the FONOP is to maintain international law and challenge any excessive maritime claims of countries. The current development seems unusual because this is the first time in recent memory that the US navy has publicly acknowledged that a military ship has entered India’s EEZ. Except for 2018, all previous reports show that there have been multiple intrusions without prior consent in a single year by the US military into India’s EEZ. But the FONOP releases challenged these claims in its annual reports every year. While they were documented annually, the U.S. Department of Defence had not publicised these operations related to India on a real-time basis.

What is an excessive maritime claim?

To understand and answer this question, we need to ask — from where do India’s 200 nautical miles start? India has notified baselines through a 2009 gazette notification, which included straight baselines around Lakshadweep to declare a new sea area as part of the country’s territorial waters. It consists of the strategic nine-degree channel that goes through the Lakshadweep group of islands and is part of the international shipping lane connecting the Gulf of Aden to South East Asia.

According to UNCLOS, only archipelagic states, like Indonesia, can use straight baselines to enclose island groups rather than continental states like India. The United States does not recognise India’s 2009 Gazette notification but has never specifically protested at the straight baselines around Lakshadweep. The location of the latest FONOP operation has also raised concern that it could be a challenge to India’s straight baselines enclosing Lakshadweep islands.

What is an Exclusive Economic Zone?

The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is an area beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea. It extends to a maximum of 200 nautical miles from the baseline from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured. After 200 nautical miles, the sea is called the high sea and is open to all other states. Under the EEZ, a state — in this case, India — has the right and control over it. India can move its ships, fish, collect intelligence and exercise other sovereign rights.

However, under Article 58 of the UNCLOS, certain rights are enjoyed by the foreign countries in the Indian EEZ, which is where the problem arises. The 58(i) of the UNCLOS mentions the “freedoms referred to in article 87 of UNCLOS”, which deals with the high seas and the rights enjoyed by all parties, including the right to navigation. Article 87 gives power to all the states to move around the high seas, including armed ships. The right to navigation allows foreign ships to move in the Indian EEZ. The latter part of the act also spells out “other internationally lawful uses of the sea related to these freedoms.” UNCLOS states that there should be no violence and threat of violence or intelligence gathering while passing through the country’s EEZ. So, if the navigation is an “innocent passage”,—it is internationally lawful.

What is Innocent Passage?

The passage is innocent as long as it is not prejudicial to India's peace, good order or security. A foreign ship with weapons can have an innocent passage under the UNCLOS, but there are a few restrictions:

There cannot be any threat, use of force, or practice of weapons;

They cannot collect intelligence;

Nothing can board or deboard the ship;

Nothing can be loaded or unloaded.

If any of the above clauses are violated by a foreign ship, it is not considered an innocent passage and India can take measures against that party. However, UNCLOS is silent about certain aspects of the innocent passage and allows states to pass laws and regulations to fill those gaps. Such questions like ‘does a foreign ship need to take permission for an innocent passage?’ is left for states to answer.

Conclusion

Washington considers India an important ally in upholding the rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific to counter Chinese aggressive actions. A burgeoning maritime partnership is taking shape, which will undoubtedly play a major role in shaping the regional order. Despite operating several FONOPs in Indian EEZ, the USA never resorted to such harsh language is, therefore, an aberration in the long-standing bilateral maritime times. The tone and tenor of the statement leads one to believe that it could have been obliquely directed at a competitor like China and not a strategic partner like India. USA’s lack of sensitivity and visible undermining of India’s stance on the UNCLOS has certainly caused unease in India’s strategic circles. Although the issue was resolved diplomatically by both sides and did not snowball into a fall-out between the Quad partners—it still exposed their differing interpretations of key maritime issues. There is great potential for both countries to work together in the Indo-Pacific. Still, both sides must address the hiccups emerging from the divergence in their respective strategic positions in the region.

'Global super powers do not think or aim for short term goal.'

India has vast global maritime interest which is not only in IOR but beyond, PLA has expanded its overreach at a faster pace than what can be imagined. It cannot be forgotten India is located on a global center point and major Shipping routes to far east can be controlled with our efforts and out reach.

What is needed is vision in expanding Navy not only in infrastructure but also in terms of dynamic Strategy independent of Focus China. Moreover, Indian Counter Defence Strategy has always focused planning limited to Pakistan till early 2010 and Now counter China 2030.

India Should focus on 'global out reach' by making its presence felt at Maritime Forums so that our interests are protected.

About the Author

Lieutenant Commander Varun Kulshrestha is former Area Judge Advocate General, Indian Navy

He has vast experience in litigation as an Advocate. He is advisor in Defence Strategy matter to various Global Think Tanks. (India Policy and Abroad ).

Field of research- 'India policy in development of Maritime Interests and Defence Strategy' as his core subject for thesis.

His work on Naxialism in Red belt of India - Indian battle with Counter Insurgency and Counter Terrorism' has been awarded by GOI

Comments